It was my pleasure to get to write on the past, present, (and hopeful future) of high school science fairs for Asterisk.

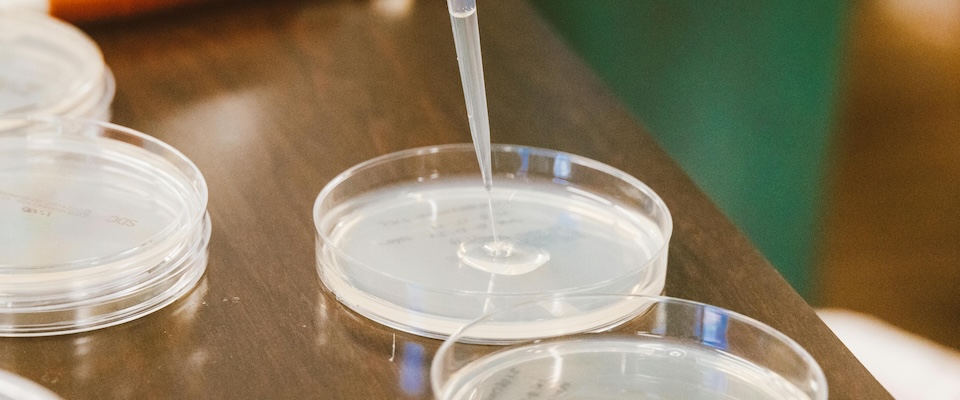

What I carried out of the lab and what enriched my life didn’t have much to do with the scientific method of “explore, wonder, hypothesize, test, repeat.” Instead, the most valuable things I learned were the virtues of reproducibility and legibility. I had very limited ability to contribute intellectually to the work I was carrying out, but I had almost unlimited potential to wreck it by mislabeling the petri dishes, forgetting to change out a pipette tip, sloppily loading the gels … or even just being lax about recording the work I did in the lab notebook that was the authoritative source of truth for the protocol.

My internship made it clear how much work it took to do something completely consistently across many partners. Even though I wasn’t knit into the culture of the lab, I still was a little awed by the trust I was given. Long after I’d left the bench behind, I remembered how important it was not just to do something right but to do it legibly right. I haven’t smelled agar plates for almost 20 years, but I still draw on old skills every time I annotate a draft for an eventual factchecker.

Ideally, students studying science should get to do some of the shadowing I did, to see how much slow, faithful, unpublishable work it takes to seek the truth. I was glad I did my internship; I just didn’t think it made much sense for me to take the results into competitions. At a science fair, I’d rather see students tackling their own questions, even if an adult could answer them better. A science fair should be more about giving intellectual and moral formation to the student than about pushing out the boundaries of what is known.

Professional internships are good for students who aspire to careers in the sciences. But everyone needs a clear sense of how we seek to understand the world. Planning out a research project and then realizing you don’t have the funds to reach the sample size you need for a sufficiently powered study is a valuable education in itself. Seeing how complex, unwieldy, and expensive the scientific process is can help clarify questions like “Why has no one checked this?” or “Why don’t scientists always agree?” Realizing halfway through a project that you wish you’d set it up differently is ok.

I’d like science fairs to be less competitive and more playful. They should give students the opportunity to lean hard into subskills of scientific literacy and informed curiosity. Fairs should be realistic that students mostly cannot execute world-class research, especially within the span of a year or two.